Shadowrun was my first real roleplaying game. While I’d played BattleTech before and I knew about Dungeons & Dragons growing up, Shadowrun was my real first introduction to tabletop roleplaying. So you can imagine that I have high expectations for a new edition of the game of cyberpunk and urban fantasy. The good news is the rules for this edition are probably the most streamlined with all the depth I’d expect without the unnecessary complications that made previous editions feel intimidating.

A quick primer for those who may not know about the thirty-year-old game. Shadowrun takes place in a world about sixty years in the future from whenever the book in question was written (give or take six months). Magic returned to the world in 2011 bringing with it dragons, elves, dwarves, orks, trolls, mages, shaman, spirits, and more. Meanwhile, megacorporations began to dominate a world of sociopolitical change, gaining extraterritoriality and becoming almost nation-states unto themselves. The internet evolved into the Matrix, a world of wireless augmented and virtual reality and permeates every aspect of daily life, for good or for ill.

You play as shadowrunners, people with very useful skills and abilities who exist outside the oppressive system and off the grid who function as deniable assets in the constant competition between the megacorporations. Your team is usually hired by a Mr. Johnson (a generic pseudonym for corporate executives) to perform or prevent acts of corporate espionage like stealing data or prototypes, extracting or protecting key employees, sabotaging projects or research, or basically any other task the corporations need doing that they don’t want to dirty their hands with themselves.

Right out of the gate, this rulebook makes its writing tone clear – this is a very conversationally-written book as opposed to the almost technical manual level of coldness you see in many other roleplaying rulebooks. The book even tells you what chapters you can safely skip or skim over if you’re a returning player to save time, though it might be in your interest to not skim too much as there are some changes to this edition.

One of the sections suggested to skip is the history and setting description chapter “The Life You Have Left”, which gives an overview of the Shadowrun world both in the big history-changing moments (with a focus on the metaplot events from previous editions) as well as what the world itself is like with both the advanced technology and the return of magic. It’s also written first-person by an unnamed character living in the Shadowrun world, so you get an impression of what characters in the setting think and feel about what’s going on around them. There are quite a few little touches like that scattered throughout the book that help put you in the mind of your characters who live in this world.

The game uses a D6 dice pool with the pool made of typically of a skill and an attribute, like Firearms + Agility to attack with a gun. While there are some modifiers to add or subtract dice from the dice pool, most of the modifiers come through the use of the Edge System, which I will get to later as it’s one of the core mechanics of the game. Any dice which come up a 5 or 6 are considered a “hit”, with more hits being good. If half or more of the dice come up 1, you have a “glitch” which is something bad happening even if you succeed at the test. If you have a glitch with no hits, that is a “critical glitch” which is a Very Bad Thing.

There’s four major types of tests. Simple tests are made against a set threshold, like Athletics + Agility (3) meaning your dice pool would come from your Athletics skill and Agility attribute, requiring three hits to succeed at the test. An opposed test is where two characters are competing with one another, such as Stealth + Agility vs Perception + Intuition to hide or find someone hiding, with the most hits succeeding. Extended tests work like simple tests only they take place over a period of time. Every time you retry the test, it takes a certain amount of time and your dice pool is reduced by 1, but you add your hits together to see how long it takes to complete the task. Finally there are teamwork tests that allow multiple characters to work together to accomplish a task. One character is the Team Leader who makes the final skill test, while everyone else are Helpers who add their hits on the test to the Team Leader’s dice pool.

There are no classes in Shadowrun as character creation is completely freeform. However, there are various roles characters tend to fall into. One of my few nitpicks about the book is they present these roles almost as though they’re classes, which may limit what some new players think they can do. Typically you have the face character who does most of the talking, the tech person who handles all the hacking, a magically active person, and a combat person. The thing is that roles can overlap, like a decker who can also do social engineering or a combat-focused mage.

Some of these roles are also rather specific to Shadowrun so I should probably explain them. Deckers plug their brains into specialized computers called cyberdecks that allow them to hack other electronic devices. Street samurai is a bit of an artifact of an earlier time with the more 1980s and very early 1990s influence of cyberpunk, but they are the combat experts who use cyberwear and bioware to enhance their physical abilities. There are also magical-based versions of each of these characters, the technomancer and adept respectively. Finally, there are riggers who use their brains to directly control vehicles and drones.

Your character will have between ten and eleven attributes, four Physical attributes (Body, Agility, Reaction, and Strength), four Mental attributes (Willpower, Logic, Intuition, and Charisma), plus two or three Special attributes (every character has an Essence and Edge attribute, while magically active characters will have a Magic attribute and technomancers will have a Resonance attribute). You also have your Initiative which is your Reaction + Intuition and between 1d6 and 5d6, depending on powers and other enhancements. This may seem like a lot of attributes, but the minor differences and how they can be combined with skills make for a lot more nuance in player choice.

There are also only nineteen skills in the game (not counting knowledge or language skills). While this is a vastly reduced skill list from previous editions, especially for a game with a system that’s based mostly around skills. However, it doesn’t feel as limiting as each skill feels useful regardless of the situation and there’s less overlap between skills. It’s clear what each skill covers and which skills you’ll want for a specific build. There are also specializations to add more nuance to the skill system that has a rather low cost, letting you get a +2 bonus for a specific subset of a skill (like a specific type of gun for Firearms like shotgun or pistol).

Now that we’ve got most of the terms out of the way, let’s talk about character creation. This is done by a Priority Table where you have five categories that you assign the priority A, B, C, D, or E. Attributes, Skills, and Resources set the number of attribute points, skill points, and starting nuyen (the currency of the Shadowrun world) and are pretty straight-forward. The metatype is where you decide if you’re going to play a human, ork, dwarf, elf, or troll along with a number of “adjustment points”. These points are used to raise your Edge, Magic or Resonance, and possibly mental or physical attributes based on your metatype. Finally, there’s the Magic or Resonance priority which sets your base Magic or Resonance. You also get 50 karma to spend, which is identical to how they’re spent as earned experience points as you play to upgrade your skills and attributes. There are also positive and negative qualities to further customize your character with specific bonuses and flaws that cost karma or provide more karma during character creation.

Character creation is still a little time consuming, but not nearly what it’s been in previous editions. My first character took me a bit over an hour to make, which sounds like a long time but that’s also how long it takes me to make characters in 3rd and 4th Edition, which are editions I’m intimately familiar with while this was my first time creating a character in 6th. My second took me closer to thirty minutes. Honestly, most of the time is spent spending money. You can only take 5000¥ from character creation into the game, so if you take Priority A for 450,000¥ (which is frequent for street samurai, deckers, and riggers because of how expensive their implants and equipment are), you eventually reach a point where you’ve bought everything you really need but still have tens of thousands of nuyen left you need to dump somewhere. Really, though, who doesn’t love shopping? It’s one of the most fun parts of Shadowrun character creation to me.

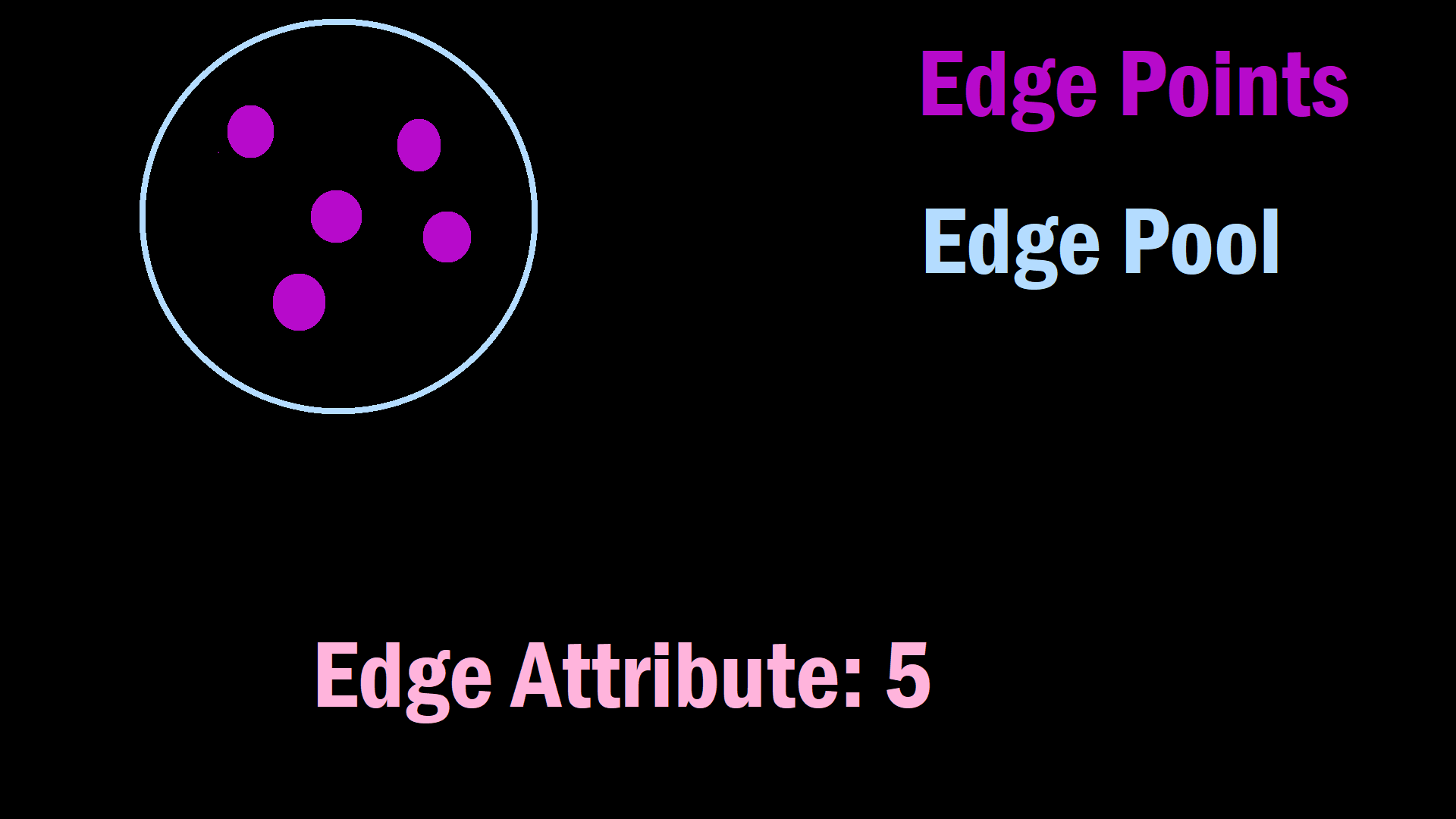

Encounters are based around a new system called Edge. I’m going to just say what it is, then try to explain it because it gets a little confusing. Your Edge Attribute sets your starting Edge Pool of Edge Points that you can spend on Edge Boosts or Edge Actions during your turn. I really wish they’d used terms that weren’t so easy to confuse, but ever since the Beginner Box came out I haven’t been able to think of a different way to do it so let me try to explain using a very crude drawing.

You have a pool of points of Edge that you can draw from during tests to get different bonuses or enhance actions. Edge Boosts costs between 1 and 5 Edge and let you get different effects on the roll like re-rolling failed dice or buying an automatic hit. Edge Actions are specific actions you can take in addition to a normal action that let you do better, like firing from behind total cover without needing to leave cover. You gain Edge by having a distinct advantage over your opponent or by having gear, cyberware, powers, spells, or other abilities that give you edge in specific circumstances. You can only have a maximum of 7 Edge at a time and can only use one Edge Boost or Edge Action per round, so players are highly encouraged to spend Edge constantly and in different ways.

Frankly, I love the new Edge system. It adds a layer of complexity to the game without making it more complicated to understand. The depth from the variety of choices you have makes encounters feel more dynamic and gives players more options without bogging them down in a big list of keywords leading to analysis paralysis. The system seems perfectly crafted to encourage players to use the points rather than horde them and push players to try things in an encounter to get more Edge they normally wouldn't risk. There's a wide range of options for not just combat, but social encounters, decking, magic, and more that make characters feel more unique within their niche. Because the system is so built around this new Edge system, it will be the make-or-break moment for many people with this edition.

The action economy of the game is split into two action types: Major and Minor. You get one Major and one Minor action per round and one more Minor action per die of Initiative you have (since every character starts with +1d6 Initiative, that means they get two Minor actions). For characters with a large Initiative bonus through cyberware or other abilities, they can trade four Minor actions for a single Major action. Actions are also labeled as (I)nitiative actions you can only take on your turn during initiative or (A)nytime even if it’s not your turn. This also reduces the analysis paralysis that frequently comes with this sort of system. You know, when players look at the actions they have available to them and waste a lot of time in combat trying to find something to do with every single action available lest they “waste” them. While there are only a handful of (A)nytime actions, the ones there are useful enough that leaving one or two minor actions unspent on your turn feels less like wasting them and more like saving them.

The rest of the game is split mainly into four subcategories of rules: Combat, Magic, Decking, and Rigging. One thing this edition does well is unifying these four systems so they don’t feel like four separate games just tacked into the same book, just minor variations of those rules and maybe one or two unique systems for each. But on the whole, the process for casting a spell, shooting a gun, or hacking a commlink is essentially the same. The only difference is which skills and attributes are used and how the after-effects work. This parallel is most clear in technomancers (people who are able to deck without a deck) where their rules for complex forms and sprites are almost exactly the same as using Sorcery to cast spells and Conjuring to summon spirits respectively. This unity makes it far easier for gamemasters to be able to effectively run the game as well as allows players to change between characters more easily as they don’t have to learn an entirely new rules system just for their character.

Every task under each system follows the same general pattern (and social encounters work this way too, but they didn’t get their own chapter): Declare your action, determine your dice pool for the opposed check, see if either side gets any points of Edge, make your rolls and spend Edge, determine the results. There might be an extra step like a mage having to roll for drain after casting a spell or a decker calculating their Overwatch Score, but that’s essentially all there is to it.

I don’t want to go into detail about each of the four systems, but I do want talk a bit about Magic and Decking as they’re the two most misleading chapters in terms of complexity. The Magic chapter feels on first reading to be lacking. There are only 72 spells in the game and many of them are basically variations on another spell. Fireball is the area effect version of flamestrike, and the Shape spell has four different versions that do the same thing except for different materials (metal, plastic, stone, and wood). This feels like there’s not a lot here but what spells there are cover pretty much anything you’d want to do. I mean do you really need a dozen different spells to do stun damage to the target?

Conversely, the Decking section can feel a bit overwhelming with the list of specific Matrix actions. However, most of the actions are just normal things we do with computers today. In order to read this review, you had to Matrix Search to locate the EN World website, Enter Host to open the site, Matrix Perception to see this review listed on the front page, Edit File to view it, and if you leave a comment you’ll be using Send Message. Other actions are very Hollywood Hacking style actions you’ve seen a thousand times in technothrillers and poorly-written police procedurals. Hack the firewall! Run the decrypt! Jam their signal! Run a Trace! It’s really not as complicated as it looks and each action clearly outlines what it does and it’s all things more familiar than you’d think.

One thing I’d like to praise this book for especially that doesn’t really affect the rules so much are the two short stories included. “Four Square” by CZ Wright is a bit confusing to read because it switches from third to first person and it takes a bit to figure out what’s going on. But once you get that the first-person sections are from Rose flashing back to a recent previous run she took herself and the third-person sections are her talking to a new runner team she’s looking to join, it’s a decent introduction to how shadowrunners work. The other short story, however, may be one of my favorites of all time for the setting. “The Way Up” by Kevin Czarnecki isn’t about a shadowrunner, it’s about a Mr. Johnson, the anonymous corporate types who hire shadowrunners. It works to flesh out the world and to humanize a type of character that, by their very role in the game world, meant to be anonymous and faceless. The placement of this story right before the Combat section also amuses me as frequently players will plot how to kill their Mr. Johnson at the start of the run when they’re inevitably betrayed, so this short story humanizing the Mr. Johnson comes right before the rules used to take them out.

There are some problems with the Shadowrun Sixth World Core Rulebook, and most of these feel like they’re issues with editing. One of the stated design goals for the core rulebook was to get it back down to closer to 300 pages rather than the almost 400 pages of 4th Edition and almost 500 pages of 5th Edition. And while they managed to get the book down to only 322 pages, it did add some confusion. There are a few parts of the rules that you can only know if you’ve played a previous edition of the game and remember those rules or if you reverse-engineer them from other sections of the book.

For example, nowhere in the entire book does it state that characters start with an Essence attribute of 6. You just have to know that from previous editions or studying the pregenerated characters in the Archetypes chapter. The damage from an unarmed strike isn’t listed anywhere either and must be reverse-engineered by looking at the damage from gear like brass knuckles or bone lacing cyberware, the grappling rules, and the Killing Hands power of the adept. In case you need to know, it’s (Strength / 2) Stun.

Another issue is that not all of the gear you can buy is located in the gear section, nor are all the rules concerning gear. Rigger Command Consoles are basically highly modified commlinks that allow riggers to control vehicles with their minds and are essential to any rigger character. They’re not in the gear chapter. Anywhere. They’re on p. 197 of the Rigger chapter. None of the drugs or toxins are in the gear chapter either, even though they’re mentioned several times in gear like darts or capsule rounds. They have a table among all the other tables in the back of the book on p. 312. Cybereyes and cyberears have a Capacity rating that limits how many enhancements they can have, but the book doesn’t tell you that you don’t have to pay additional Essence for those enhancements (another rule you can only get by reverse-engineering the pregen archetypes). There are also rules about programs for cyberdecks, commlinks, and rigger command consoles that aren’t really explained in one place so you have to read both the Gear section and the Matrix or Rigging chapters flipping back and forth when you’re making your character to make sure you’re not missing anything.

The tables at the end also could use with some work. While the eight pages of tables from throughout the book make a great reference so you don’t have to constantly flip around, a few of the most important ones don’t have all the information they could. For example, the list of Actions doesn’t tell whether they’re (I)nitiative actions or (A)nytime actions and the list of Matrix actions don’t list which are (L)egal and which are (I)llegal. Since these indicated elsewhere in the book by the one-letter codes, it seems something that could’ve easily been added to these tables as an added reference point and help prevent the need to flip around for rules references.

Overall, though, the book is great and one of the better written and organized core rulebooks Shadowrun’s had. It also feels like a rulebook and system written for the modern tabletop landscape. The Edge system adds a lot of depth to the game without adding too much additional complexity and allows Shadowrun to keep the crunchy feel of the rules while still embracing the push toward more dynamic and narrative-driven systems. There are just enough options to make most any character you want, but you still want more and can see where there’s room to expand for future products. The book could do with a few more rules examples, but the majority of brand new players these days will be likely to skip over those in favor of listening to an Actual Play podcast or watching a Twitch stream of a game being played while older players will remember how the rules worked in previous editions.

The Shadowrun Sixth World Core Rulebook is available now in PDF from DriveThruRPG for $19.99 which includes the updated errata from August. You can pre-order the hardcover in the Catalyst Game Labs store for $49.99 (which includes a PDF), but the first printing of the hardcover does not include the ten-page August errata.

A quick primer for those who may not know about the thirty-year-old game. Shadowrun takes place in a world about sixty years in the future from whenever the book in question was written (give or take six months). Magic returned to the world in 2011 bringing with it dragons, elves, dwarves, orks, trolls, mages, shaman, spirits, and more. Meanwhile, megacorporations began to dominate a world of sociopolitical change, gaining extraterritoriality and becoming almost nation-states unto themselves. The internet evolved into the Matrix, a world of wireless augmented and virtual reality and permeates every aspect of daily life, for good or for ill.

You play as shadowrunners, people with very useful skills and abilities who exist outside the oppressive system and off the grid who function as deniable assets in the constant competition between the megacorporations. Your team is usually hired by a Mr. Johnson (a generic pseudonym for corporate executives) to perform or prevent acts of corporate espionage like stealing data or prototypes, extracting or protecting key employees, sabotaging projects or research, or basically any other task the corporations need doing that they don’t want to dirty their hands with themselves.

Right out of the gate, this rulebook makes its writing tone clear – this is a very conversationally-written book as opposed to the almost technical manual level of coldness you see in many other roleplaying rulebooks. The book even tells you what chapters you can safely skip or skim over if you’re a returning player to save time, though it might be in your interest to not skim too much as there are some changes to this edition.

One of the sections suggested to skip is the history and setting description chapter “The Life You Have Left”, which gives an overview of the Shadowrun world both in the big history-changing moments (with a focus on the metaplot events from previous editions) as well as what the world itself is like with both the advanced technology and the return of magic. It’s also written first-person by an unnamed character living in the Shadowrun world, so you get an impression of what characters in the setting think and feel about what’s going on around them. There are quite a few little touches like that scattered throughout the book that help put you in the mind of your characters who live in this world.

The game uses a D6 dice pool with the pool made of typically of a skill and an attribute, like Firearms + Agility to attack with a gun. While there are some modifiers to add or subtract dice from the dice pool, most of the modifiers come through the use of the Edge System, which I will get to later as it’s one of the core mechanics of the game. Any dice which come up a 5 or 6 are considered a “hit”, with more hits being good. If half or more of the dice come up 1, you have a “glitch” which is something bad happening even if you succeed at the test. If you have a glitch with no hits, that is a “critical glitch” which is a Very Bad Thing.

There’s four major types of tests. Simple tests are made against a set threshold, like Athletics + Agility (3) meaning your dice pool would come from your Athletics skill and Agility attribute, requiring three hits to succeed at the test. An opposed test is where two characters are competing with one another, such as Stealth + Agility vs Perception + Intuition to hide or find someone hiding, with the most hits succeeding. Extended tests work like simple tests only they take place over a period of time. Every time you retry the test, it takes a certain amount of time and your dice pool is reduced by 1, but you add your hits together to see how long it takes to complete the task. Finally there are teamwork tests that allow multiple characters to work together to accomplish a task. One character is the Team Leader who makes the final skill test, while everyone else are Helpers who add their hits on the test to the Team Leader’s dice pool.

There are no classes in Shadowrun as character creation is completely freeform. However, there are various roles characters tend to fall into. One of my few nitpicks about the book is they present these roles almost as though they’re classes, which may limit what some new players think they can do. Typically you have the face character who does most of the talking, the tech person who handles all the hacking, a magically active person, and a combat person. The thing is that roles can overlap, like a decker who can also do social engineering or a combat-focused mage.

Some of these roles are also rather specific to Shadowrun so I should probably explain them. Deckers plug their brains into specialized computers called cyberdecks that allow them to hack other electronic devices. Street samurai is a bit of an artifact of an earlier time with the more 1980s and very early 1990s influence of cyberpunk, but they are the combat experts who use cyberwear and bioware to enhance their physical abilities. There are also magical-based versions of each of these characters, the technomancer and adept respectively. Finally, there are riggers who use their brains to directly control vehicles and drones.

Your character will have between ten and eleven attributes, four Physical attributes (Body, Agility, Reaction, and Strength), four Mental attributes (Willpower, Logic, Intuition, and Charisma), plus two or three Special attributes (every character has an Essence and Edge attribute, while magically active characters will have a Magic attribute and technomancers will have a Resonance attribute). You also have your Initiative which is your Reaction + Intuition and between 1d6 and 5d6, depending on powers and other enhancements. This may seem like a lot of attributes, but the minor differences and how they can be combined with skills make for a lot more nuance in player choice.

There are also only nineteen skills in the game (not counting knowledge or language skills). While this is a vastly reduced skill list from previous editions, especially for a game with a system that’s based mostly around skills. However, it doesn’t feel as limiting as each skill feels useful regardless of the situation and there’s less overlap between skills. It’s clear what each skill covers and which skills you’ll want for a specific build. There are also specializations to add more nuance to the skill system that has a rather low cost, letting you get a +2 bonus for a specific subset of a skill (like a specific type of gun for Firearms like shotgun or pistol).

Now that we’ve got most of the terms out of the way, let’s talk about character creation. This is done by a Priority Table where you have five categories that you assign the priority A, B, C, D, or E. Attributes, Skills, and Resources set the number of attribute points, skill points, and starting nuyen (the currency of the Shadowrun world) and are pretty straight-forward. The metatype is where you decide if you’re going to play a human, ork, dwarf, elf, or troll along with a number of “adjustment points”. These points are used to raise your Edge, Magic or Resonance, and possibly mental or physical attributes based on your metatype. Finally, there’s the Magic or Resonance priority which sets your base Magic or Resonance. You also get 50 karma to spend, which is identical to how they’re spent as earned experience points as you play to upgrade your skills and attributes. There are also positive and negative qualities to further customize your character with specific bonuses and flaws that cost karma or provide more karma during character creation.

Character creation is still a little time consuming, but not nearly what it’s been in previous editions. My first character took me a bit over an hour to make, which sounds like a long time but that’s also how long it takes me to make characters in 3rd and 4th Edition, which are editions I’m intimately familiar with while this was my first time creating a character in 6th. My second took me closer to thirty minutes. Honestly, most of the time is spent spending money. You can only take 5000¥ from character creation into the game, so if you take Priority A for 450,000¥ (which is frequent for street samurai, deckers, and riggers because of how expensive their implants and equipment are), you eventually reach a point where you’ve bought everything you really need but still have tens of thousands of nuyen left you need to dump somewhere. Really, though, who doesn’t love shopping? It’s one of the most fun parts of Shadowrun character creation to me.

Encounters are based around a new system called Edge. I’m going to just say what it is, then try to explain it because it gets a little confusing. Your Edge Attribute sets your starting Edge Pool of Edge Points that you can spend on Edge Boosts or Edge Actions during your turn. I really wish they’d used terms that weren’t so easy to confuse, but ever since the Beginner Box came out I haven’t been able to think of a different way to do it so let me try to explain using a very crude drawing.

You have a pool of points of Edge that you can draw from during tests to get different bonuses or enhance actions. Edge Boosts costs between 1 and 5 Edge and let you get different effects on the roll like re-rolling failed dice or buying an automatic hit. Edge Actions are specific actions you can take in addition to a normal action that let you do better, like firing from behind total cover without needing to leave cover. You gain Edge by having a distinct advantage over your opponent or by having gear, cyberware, powers, spells, or other abilities that give you edge in specific circumstances. You can only have a maximum of 7 Edge at a time and can only use one Edge Boost or Edge Action per round, so players are highly encouraged to spend Edge constantly and in different ways.

Frankly, I love the new Edge system. It adds a layer of complexity to the game without making it more complicated to understand. The depth from the variety of choices you have makes encounters feel more dynamic and gives players more options without bogging them down in a big list of keywords leading to analysis paralysis. The system seems perfectly crafted to encourage players to use the points rather than horde them and push players to try things in an encounter to get more Edge they normally wouldn't risk. There's a wide range of options for not just combat, but social encounters, decking, magic, and more that make characters feel more unique within their niche. Because the system is so built around this new Edge system, it will be the make-or-break moment for many people with this edition.

The action economy of the game is split into two action types: Major and Minor. You get one Major and one Minor action per round and one more Minor action per die of Initiative you have (since every character starts with +1d6 Initiative, that means they get two Minor actions). For characters with a large Initiative bonus through cyberware or other abilities, they can trade four Minor actions for a single Major action. Actions are also labeled as (I)nitiative actions you can only take on your turn during initiative or (A)nytime even if it’s not your turn. This also reduces the analysis paralysis that frequently comes with this sort of system. You know, when players look at the actions they have available to them and waste a lot of time in combat trying to find something to do with every single action available lest they “waste” them. While there are only a handful of (A)nytime actions, the ones there are useful enough that leaving one or two minor actions unspent on your turn feels less like wasting them and more like saving them.

The rest of the game is split mainly into four subcategories of rules: Combat, Magic, Decking, and Rigging. One thing this edition does well is unifying these four systems so they don’t feel like four separate games just tacked into the same book, just minor variations of those rules and maybe one or two unique systems for each. But on the whole, the process for casting a spell, shooting a gun, or hacking a commlink is essentially the same. The only difference is which skills and attributes are used and how the after-effects work. This parallel is most clear in technomancers (people who are able to deck without a deck) where their rules for complex forms and sprites are almost exactly the same as using Sorcery to cast spells and Conjuring to summon spirits respectively. This unity makes it far easier for gamemasters to be able to effectively run the game as well as allows players to change between characters more easily as they don’t have to learn an entirely new rules system just for their character.

Every task under each system follows the same general pattern (and social encounters work this way too, but they didn’t get their own chapter): Declare your action, determine your dice pool for the opposed check, see if either side gets any points of Edge, make your rolls and spend Edge, determine the results. There might be an extra step like a mage having to roll for drain after casting a spell or a decker calculating their Overwatch Score, but that’s essentially all there is to it.

I don’t want to go into detail about each of the four systems, but I do want talk a bit about Magic and Decking as they’re the two most misleading chapters in terms of complexity. The Magic chapter feels on first reading to be lacking. There are only 72 spells in the game and many of them are basically variations on another spell. Fireball is the area effect version of flamestrike, and the Shape spell has four different versions that do the same thing except for different materials (metal, plastic, stone, and wood). This feels like there’s not a lot here but what spells there are cover pretty much anything you’d want to do. I mean do you really need a dozen different spells to do stun damage to the target?

Conversely, the Decking section can feel a bit overwhelming with the list of specific Matrix actions. However, most of the actions are just normal things we do with computers today. In order to read this review, you had to Matrix Search to locate the EN World website, Enter Host to open the site, Matrix Perception to see this review listed on the front page, Edit File to view it, and if you leave a comment you’ll be using Send Message. Other actions are very Hollywood Hacking style actions you’ve seen a thousand times in technothrillers and poorly-written police procedurals. Hack the firewall! Run the decrypt! Jam their signal! Run a Trace! It’s really not as complicated as it looks and each action clearly outlines what it does and it’s all things more familiar than you’d think.

One thing I’d like to praise this book for especially that doesn’t really affect the rules so much are the two short stories included. “Four Square” by CZ Wright is a bit confusing to read because it switches from third to first person and it takes a bit to figure out what’s going on. But once you get that the first-person sections are from Rose flashing back to a recent previous run she took herself and the third-person sections are her talking to a new runner team she’s looking to join, it’s a decent introduction to how shadowrunners work. The other short story, however, may be one of my favorites of all time for the setting. “The Way Up” by Kevin Czarnecki isn’t about a shadowrunner, it’s about a Mr. Johnson, the anonymous corporate types who hire shadowrunners. It works to flesh out the world and to humanize a type of character that, by their very role in the game world, meant to be anonymous and faceless. The placement of this story right before the Combat section also amuses me as frequently players will plot how to kill their Mr. Johnson at the start of the run when they’re inevitably betrayed, so this short story humanizing the Mr. Johnson comes right before the rules used to take them out.

There are some problems with the Shadowrun Sixth World Core Rulebook, and most of these feel like they’re issues with editing. One of the stated design goals for the core rulebook was to get it back down to closer to 300 pages rather than the almost 400 pages of 4th Edition and almost 500 pages of 5th Edition. And while they managed to get the book down to only 322 pages, it did add some confusion. There are a few parts of the rules that you can only know if you’ve played a previous edition of the game and remember those rules or if you reverse-engineer them from other sections of the book.

For example, nowhere in the entire book does it state that characters start with an Essence attribute of 6. You just have to know that from previous editions or studying the pregenerated characters in the Archetypes chapter. The damage from an unarmed strike isn’t listed anywhere either and must be reverse-engineered by looking at the damage from gear like brass knuckles or bone lacing cyberware, the grappling rules, and the Killing Hands power of the adept. In case you need to know, it’s (Strength / 2) Stun.

Another issue is that not all of the gear you can buy is located in the gear section, nor are all the rules concerning gear. Rigger Command Consoles are basically highly modified commlinks that allow riggers to control vehicles with their minds and are essential to any rigger character. They’re not in the gear chapter. Anywhere. They’re on p. 197 of the Rigger chapter. None of the drugs or toxins are in the gear chapter either, even though they’re mentioned several times in gear like darts or capsule rounds. They have a table among all the other tables in the back of the book on p. 312. Cybereyes and cyberears have a Capacity rating that limits how many enhancements they can have, but the book doesn’t tell you that you don’t have to pay additional Essence for those enhancements (another rule you can only get by reverse-engineering the pregen archetypes). There are also rules about programs for cyberdecks, commlinks, and rigger command consoles that aren’t really explained in one place so you have to read both the Gear section and the Matrix or Rigging chapters flipping back and forth when you’re making your character to make sure you’re not missing anything.

The tables at the end also could use with some work. While the eight pages of tables from throughout the book make a great reference so you don’t have to constantly flip around, a few of the most important ones don’t have all the information they could. For example, the list of Actions doesn’t tell whether they’re (I)nitiative actions or (A)nytime actions and the list of Matrix actions don’t list which are (L)egal and which are (I)llegal. Since these indicated elsewhere in the book by the one-letter codes, it seems something that could’ve easily been added to these tables as an added reference point and help prevent the need to flip around for rules references.

Overall, though, the book is great and one of the better written and organized core rulebooks Shadowrun’s had. It also feels like a rulebook and system written for the modern tabletop landscape. The Edge system adds a lot of depth to the game without adding too much additional complexity and allows Shadowrun to keep the crunchy feel of the rules while still embracing the push toward more dynamic and narrative-driven systems. There are just enough options to make most any character you want, but you still want more and can see where there’s room to expand for future products. The book could do with a few more rules examples, but the majority of brand new players these days will be likely to skip over those in favor of listening to an Actual Play podcast or watching a Twitch stream of a game being played while older players will remember how the rules worked in previous editions.

The Shadowrun Sixth World Core Rulebook is available now in PDF from DriveThruRPG for $19.99 which includes the updated errata from August. You can pre-order the hardcover in the Catalyst Game Labs store for $49.99 (which includes a PDF), but the first printing of the hardcover does not include the ten-page August errata.